Trauma: Penetrating Thoracic Trauma

Article Sections

Introduction

Penetrating trauma to the chest is a critical emergency that arises from various mechanisms, such as stab wounds, gunshot injuries, or other forms of violence. This type of trauma can result in a range of life-threatening injuries, including pneumothorax, hemothorax, cardiac tamponade, lung lacerations, and great vessel injuries. The management of penetrating chest trauma often requires a rapid assessment and intervention, which may include surgical procedures to control bleeding, repair injuries, or decompress the pleural space. In contrast to blunt trauma, which may lead to injuries such as rib fractures and pulmonary contusions that are often managed nonoperatively, penetrating trauma frequently necessitates immediate surgical intervention due to the direct and often catastrophic nature of the injuries involved. Early recognition and prompt management are crucial in mitigating complications and improving patient outcomes in cases of penetrating chest trauma.

Anatomy

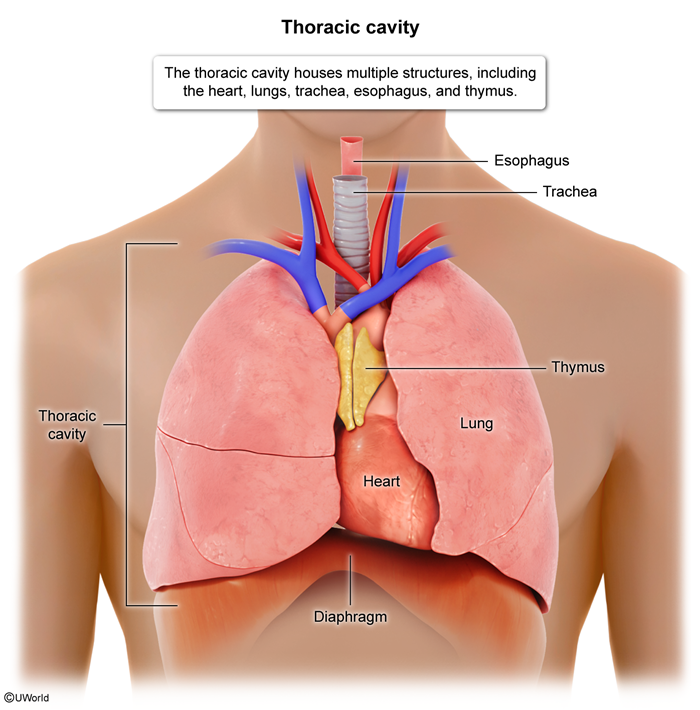

The thoracic cavity (Figure 1) is bordered by the clavicles superiorly, the diaphragm inferiorly, the rib cages laterally, the sternum and ribs anteriorly, and the ribs and vertebrae posteriorly.

- Central penetrating wounds inside "the box"—delineated superiorly by the clavicles, inferiorly by the costal margins, and laterally by the nipples—are particularly dangerous because of the underlying heart and mediastinal structures.

- Injuries occurring below the scapula (seventh intercostal space) posteriorly or nipple line (fourth intercostal space) anteriorly can potentially penetrate the diaphragm, causing thoracoabdominal injuries.

Although the majority of penetrating injuries to the thoracic cavity are limited to structures in the thorax, some (up to 20%) may also include abdominal injuries.

Initial evaluation

The assessment of penetrating trauma begins with the primary survey (ABCDE approach) of trauma management made widely known in advanced trauma life support (ATLS). The goal of the primary survey is to address injuries that are the most immediately life-threatening. The primary survey in penetrating trauma is similar to blunt trauma.

- Airway: Address any critical airway compromise (eg, occlusion). The neck should be carefully examined because this is a common area where obstruction can occur (eg, from hematoma).

- Breathing: Assess for signs of pneumothorax, hemothorax, or tension pneumothorax, which are common in penetrating chest trauma. Signs of respiratory distress, asymmetric breath sounds, and jugular venous distention may indicate these conditions. If one of these conditions is identified, it should be addressed before moving on in the survey.

- Circulation: Hypotension in penetrating trauma often results from hemorrhage. Hemorrhage should be immediately controlled when possible (eg, direct compression). Pericardial tamponade and tension pneumothorax should be considered as other causes of hypotension.

- Disability: A rapid neurologic assessment with Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) should be performed.

- Exposure: Patients should be completely undressed, and the entire body should be searched for occult injuries. Areas that are often missed include the scalp, axillary folds, perineum, and, in obese patients, abdominal folds.

A more detailed description of the primary survey is described in another article.

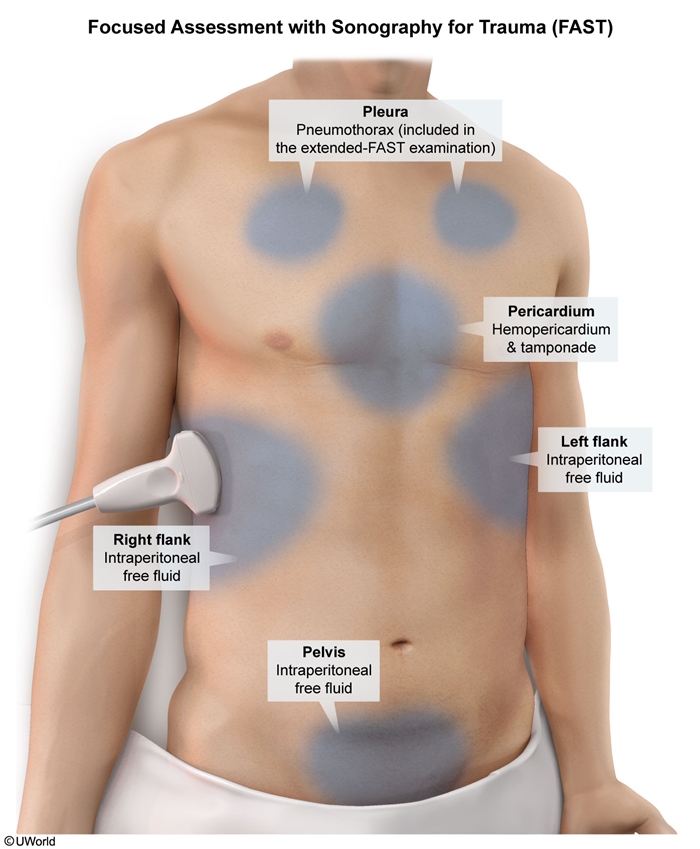

Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (E-FAST)The E-FAST is an important sonographic tool in the initial assessment of patients with penetrating chest injuries because it evaluates for the presence of free fluid or air in specific areas of the body following trauma as well as for pneumothorax and hemothorax (E-FAST includes all 4 standard FAST views (Figure 2) plus bilateral anterior lung views). A positive E-FAST is highly specific in penetrating trauma, but a negative E-FAST does not rule out intraabdominal injuries (eg, damage to the diaphragm or hollow organs), and further evaluation through repeated abdominal exams, diagnostic peritoneal lavage, CT scans, or exploratory surgery may be necessary.

Diagnostic work-up

In addition to E-FAST, most patients with penetrating trauma will require laboratory evaluation and imaging.

Laboratory evaluationAlthough laboratory results are not diagnostic and often lag behind the patient's clinical presentation, they are still important for assessing the extent of injury, guiding treatment decisions, and monitoring for complications. Tests that may be indicated in patients with penetrating trauma include: complete blood count, blood type and crossmatch, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, coagulation panel, arterial blood gas, lactate level, urinalysis, and pregnancy tests.

ImagingPatients with penetrating trauma to the chest typically have a chest x-ray (CXR). Further imaging (eg, CT, esophagogram, bronchoscopy) may be indicated depending on location of injury.

- Plain radiographs: A supine anteroposterior CXR is obtained, with an upright CXR preferred if the patient is not severely injured. Important injuries detected on CXR include pneumothorax, hemothorax, rib fractures, and retained ballistic fragments. Esophageal injuries, hemopericardium, and diaphragm injuries cannot be directly seen on CXR, but associated signs (eg, pneumomediastinum, organ herniation into thoracic cavity) may be evident.

- CT scan of the chest: Appropriate for hemodynamically stable patients with penetrating thoracic trauma and typically performed with intravenous contrast. Indications include:

- The trajectory of the object crosses the mediastinum or center of the chest.

- Signs or symptoms suggesting injury to the esophagus, tracheobronchial tree, or major blood vessels (eg, pneumomediastinum, widened mediastinum on x-ray).

- Signs or symptoms (eg, hypotension, chest pain, shortness of breath) that cannot be fully explained by a CXR.

Advantages of CT over CXR include CTs superior sensitivity and specificity in detecting pneumothorax, hemothorax, and injuries to internal thoracic structures.

Penetrating thoracic injury near mediastinal structures (eg, within "the box") requires evaluation to rule out damage to the heart, tracheobronchial tree, or esophagus. This typically involves echocardiography, along with bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy or a contrast esophagogram.

Penetrating injuries below the nipple line anteriorly and below the tip of the scapula posteriorly (suspicious for thoracoabdominal injuries) are difficult to evaluate because diaphragm movement can obscure the wound path. Imaging of the abdomen is often indicated to assess for injuries to abdominal organs (eg, liver, spleen) and major blood vessels (eg, aorta).

Clinical presentation and management

Penetrating chest trauma can cause a variety of injuries that necessitate different management.

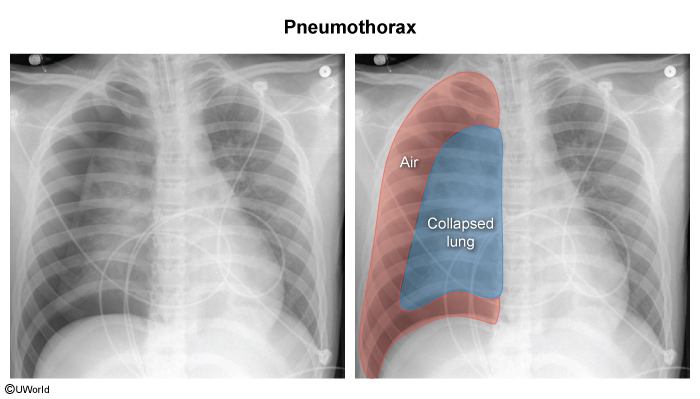

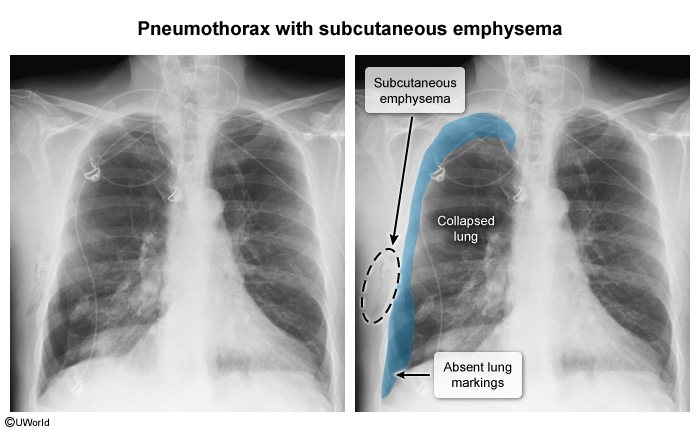

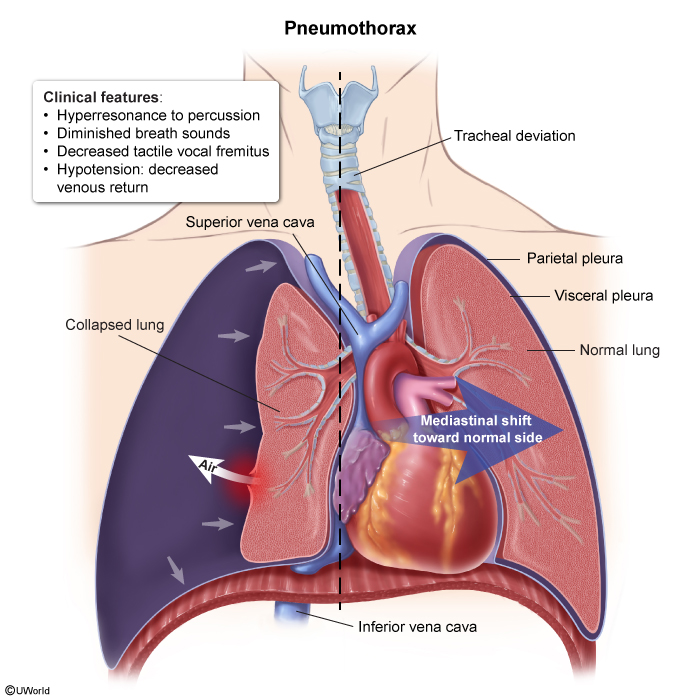

Pneumothorax- Clinical presentation: may be asymptomatic or can have dyspnea, tachypnea, pleuritic chest pain, hypoxia, unilateral diminished or absent breath sounds, or unilateral hyperresonance to percussion (Figure 3).

- Imaging: On CXR, a pneumothorax appears as a visible pleural line with absent lung markings beyond it, and the deep sulcus sign may be seen in supine patients (Image 1). On CT, pneumothorax shows air in the pleural space with a clear collapsed lung edge and no lung markings in the affected area (Image 2).

- Management: In the majority of cases, tube thoracostomy is indicated. Occasionally, a small asymptomatic pneumothorax (eg, visible on CT but not CXR) can be observed and serial CXRs obtained to follow any expansion.

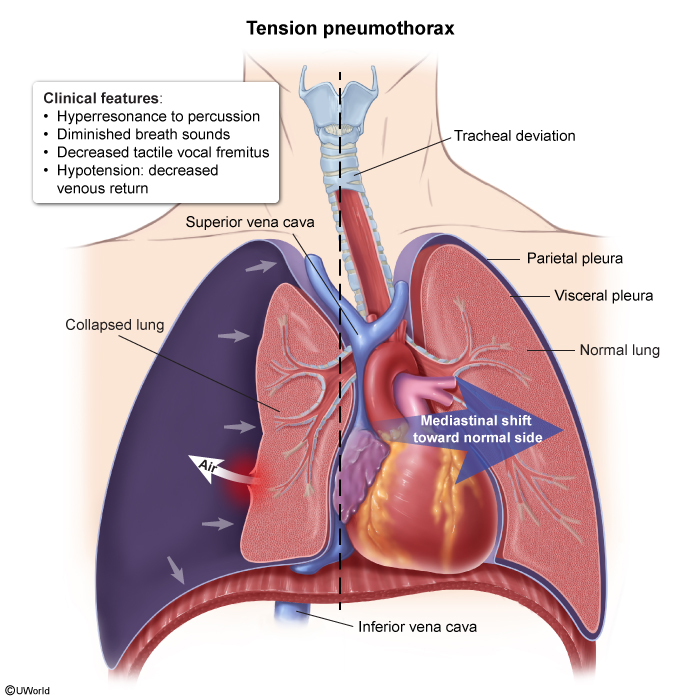

- Clinical presentation: may be characterized by acute severe dyspnea, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and neck vein distension (due to superior vena cava compression). TP develops when accumulated air (due to injured lung tissue) causes high intrathoracic pressure that compresses the vena cava and impedes cardiac venous return, resulting in decreased cardiac output and hypotension. This occurs when a one-way valve has formed, allowing air to flow into the pleural space during inspiration but trapping it during expiration (Figure 4).

- Imaging: On CXR, mediastinal shift (Image 3) away from the affected side, flattening or depression of the diaphragm, and widening of the intercostal spaces is often seen. There is also an absence of lung markings beyond the visible pleural line.

- Management: When TP is suspected, needle decompression (or, if available, emergency tube thoracostomy) should be initiated immediately, followed by placement of a tube thoracostomy (Table 1). Needle thoracostomy can be performed quickly and should precede intubation. It is typically done in the second intercostal space at the midclavicular line or the fifth intercostal space at the anterior axillary line. A long, large bore catheter should be used (eg, 14 gauge).

- Clinical presentation: Diminished breath sounds and dullness to percussion are findings consistent with hemothorax, which may result from injuries to larger intrathoracic structures (eg, aorta, hilar vessels) and/or smaller structures (eg, lung parenchyma, intercostal blood vessels). Each hemithorax can hold up to 40% of the circulating blood volume, and massive hemothorax (>1,500 mL) can present with signs of hemorrhagic shock and tracheal deviation from mass effect.

- Imaging: may appear as a homogeneous opacity in the pleural space (Image 4), typically with blunting of the costophrenic angle. In larger hemothoraces, there may be a fluid level with a meniscus sign, where the fluid line curves upward along the chest wall.

- Management: Tube thoracostomy is typically sufficient to manage hemothorax. Some patients (up to 15%) require emergency thoracotomy for extreme bleeding, including patients with initial bloody output >1,500 mL, persistent hemorrhage (eg, >200 mL/hr for >2 hours) or continuous need for blood transfusion to maintain hemodynamic stability.

- Clinical presentation: occurs due to rapid fluid accumulation in the pericardial space. Patients may have hypotension with elevated jugular venous pressure (obstructive shock due to the pericardial fluid preventing adequate cardiac contraction) as well as muffled heart sounds (Beck triad (Table 2), only seen in a minority of patients).

- Imaging: The condition is best identified on FAST, where blood will be evident in the pericardial space with evidence of right ventricular dysfunction (eg, right ventricular diastolic collapse). A CXR may not show cardiomegaly because the stiff pericardium does not have time to adapt when fluid accumulates rapidly as occurs in trauma.

- Management: Immediate pericardiocentesis or thoracotomy is indicated to prevent decompensation.

- Clinical presentation: Common symptoms of a diaphragm injury include abdominal pain (often felt in the upper abdomen), referred shoulder pain, difficulty breathing, vomiting, difficulty swallowing, or shock. However, some patients may not exhibit any symptoms, and a physical examination alone is not sufficient to exclude a diaphragmatic injury.

- Imaging: CXR (Image 5) may show abdominal organs within the chest (with or without mediastinal deviation) but is typically nondiagnostic (elevation of the hemidiaphragm may be the only abnormal finding). CT scans of the chest and abdomen may show direct signs (eg, discontinuity of the diaphragm) or indirect signs (eg, diaphragm thickening, organ herniation) of injury. Ultrasonography and MRI can also be used to diagnose the condition, but even with imaging, small tears can be difficult to recognize, and diagnosis may be delayed.

- Management: Surgical repair is indicated in all left-sided injuries and many right-sided injuries. Sometimes, small right-sided injuries can be managed nonoperatively (the liver blocks or "tamponades" the injury).

Other structures can also be injured in penetrating trauma to the chest. These include the esophagus, major vessels (eg, aorta, subclavian), and tracheobronchial tree. Injuries to these structures are discussed in a different article.

Emergency Department Thoracotomy (EDT)

Emergency department thoracotomy (EDT) is a critical procedure for resuscitating trauma patients in cardiac arrest or peri-arrest, particularly in cases of penetrating thoracic injuries. It involves opening the chest (eg, incision and rib spreading) to relieve cardiac tamponade (eg, pericardiotomy), control hemorrhage (eg, aortic cross-clamping), or provide direct cardiac massage to restore circulation. EDT should be performed only in institutions with appropriate resources (eg, trauma/cardiothoracic surgery). Overall survival rates are poor; they are slightly more favorable for patients with isolated stab wounds and signs of life upon hospital arrival.

Complications

The complications associated with penetrating chest trauma are closely linked to the organs and structures involved. Common complications include:

- Hemorrhagic shock: Rapid blood loss from major vessels in the chest can result in hemorrhagic shock. This is more common in penetrating trauma due to direct vessel disruption compared to blunt trauma, where bleeding is more likely to be contained.

- Pulmonary complications: Persistent pneumothorax, hemothorax, or empyema can occur leading to prolonged respiratory compromise and its associated complications. Widespread inflammation and lung damage from trauma can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, which can be life-threatening and require intensive care management.

- Infection and sepsis: Penetrating trauma introduces external pathogens into sterile body cavities, increasing the risk of infection and abscess formation, especially in the setting of hollow viscus (eg, bowel) perforation.

- Fistula formation: Abnormal connections can develop between organs (eg, esophagus and aorta) due to trauma, leading to complications such as massive hematemesis.

Summary

The management of penetrating trauma to the chest requires immediate intervention when life-threatening conditions are present. Rapid assessment, followed by targeted imaging, can help identify injuries that require surgical management. Compared to blunt trauma, penetrating injuries more frequently necessitate operative intervention due to the direct damage to organs and vasculature. The conceptual algorithms for management differ slightly, with penetrating injuries often requiring more aggressive surgical intervention, whereas blunt trauma is more often managed conservatively in stable patients.

Continue Learning with UWorld

Get the full Trauma: Penetrating Thoracic Trauma article plus rich visuals, real-world cases, and in-depth insights from medical experts, all available through the UWorld Medical Library.

Figures

Images