Schistosomiasis

Article Sections

Introduction

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharziasis) is a neglected tropical disease caused by parasitic trematodes (flatworms, or flukes) of genus Schistosoma. There are 3 species of clinical relevance:

- S haematobium (urinary schistosomiasis)

- S mansoni (hepatosplenic/intestinal schistosomiasis)

- S japonicum (hepatosplenic/intestinal schistosomiasis)

Their general life cycle is similar, although geographic distribution and organ involvement vary. Schistosomiasis is characterized by a granulomatous, inflammatory, and fibrotic response to Schistosoma eggs within tissues (particularly bladder, gut, liver, lungs), leading to acute and chronic manifestations (eg, bladder carcinoma, cirrhosis, and pulmonary hypertension). It remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Parasitology

Schistosoma flukes (flatworms) are prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions, particularly in areas with poor water sanitation. Their lifecycle passes between aquatic snail and human hosts. Aquatic snails are the intermediate host (developmental stage of larvae), and humans are the definitive host (reproductive and egg-laying stage).

The larvae (cercariae) are the infective form. They penetrate the skin of humans who enter contaminated water (eg, bathing, swimming, fishing). Once inside the human host, cercariae migrate through the bloodstream to various organs (primarily the bladder, intestines, liver, and lungs), where they mature into adult worms. Within these organs, adult worms mate for life (10-20 years), producing hundreds of eggs per day. The eggs are excreted into the urine if the bladder is involved (eg, S haematobium) or stool if the liver and gut are involved (eg, S mansoni and S japonicum). These eggs pollute the water supply, hatching into primitive larvae (miracidia) that infect other snails, completing the cycle.

Pathophysiology

Schistosomiasis is driven by egg-induced inflammation. Eggs become trapped in tissues (particularly in the liver, intestines, bladder, and lungs). They provoke granuloma formation and chronic inflammation, eventually inducing a fibrotic response. This involves a gradual switch between allergic immune signaling (TH2: eg, IL-4, IL-5) and fibrotic signaling (eg, IL-13, TGFβ).

Inflammation and fibrosis can cause organ-specific pathology affecting the liver (eg, cirrhosis, portal hypertension), bladder (eg, hematuria from inflammation, urinary retention from wall fibrosis, squamous cell carcinoma), lungs (eg, pulmonary hypertension), and bowel (eg, dysmotility, strictures, malabsorption).

Clinical presentation

There are 2 forms of acute Schistosoma infection:

- Schistosomal dermatitis (swimmer's itch): A local dermatitis can occur where larvae penetrate the skin (typically calves and feet). It is a delayed (ie, type IV) hypersensitivity reaction that requires repeated exposure to circarae. (In some references, swimmer's itch refers to the allergic inflammation due to burrowing schistosomal larvae from nonhuman schistosomes.)

- Acute schistosomiasis syndrome (Katayama fever): A systemic immune complex (ie, type III) hypersensitivity reaction against Schistosoma antigens that occurs ~1 month after initial larval infection. It corresponds to the start of egg production. Patients develop recurring fever (typically nocturnal), migratory urticaria (with possible angioedema), and other nonspecific symptoms resembling serum sickness (eg, arthralgias, myalgias, malaise). Peripheral blood eosinophilia (often >10%) is often present. Fleeting pulmonary infiltrates can be seen on chest x-ray as larvae pass through the pulmonary capillaries and venules. This acute syndrome typically resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks as granulomas wall off the eggs, limiting the systemic reaction.

Urinary schistosomiasis is mainly caused by S haematobium, endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East. Schistosoma eggs can cause a range of pathology in the urinary tract:

- Ureterovesical inflammation and fibrosis: Eggs implanted in the ureteral and bladder wall induce granuloma formation, leading to hematuria and pyuria. The hematuria progresses from microscopic (early stages) to grossly visible (later stages), and may be accompanied by lower urinary tract symptoms (eg, dysuria, urgency). In advanced chronic stages (eg, years), the detrusor muscle becomes fibrotic and calcified, leading to voiding dysfunction (eg, retention), hydronephrosis, and renal failure due to obstruction.

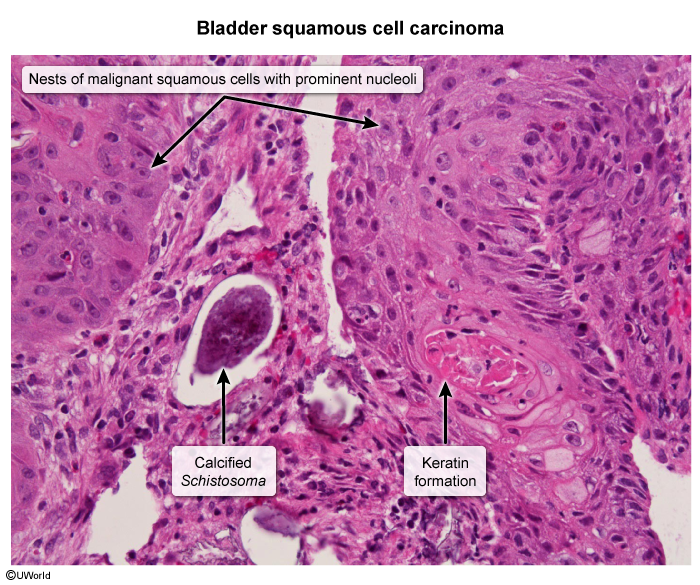

- Bladder cancer: Longstanding infection of the bladder wall induces epithelial metaplasia and can progress to bladder cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common histologic subtype, in contrast to urothelial (transitional cell) carcinoma, which is the classic form of bladder cancer (eg, associated with smoking and naphthylamine carcinogens).

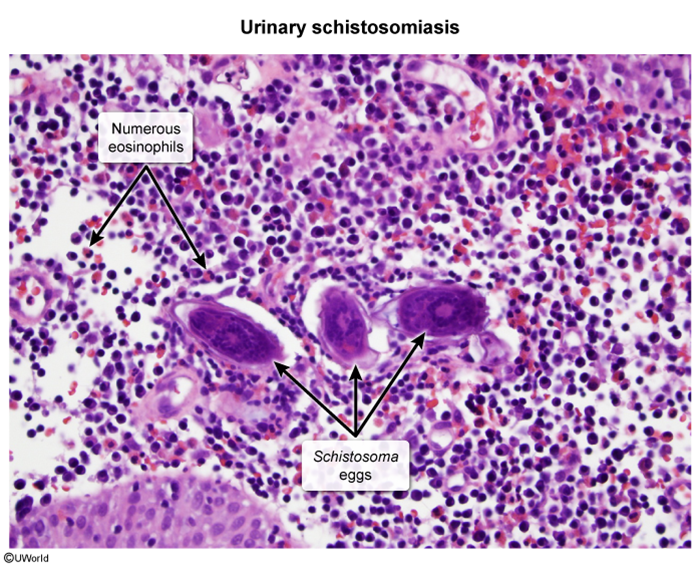

Cystoscopy and biopsy are performed for suspicious lesions (eg, thickening, polyps, masses) to rule out bladder malignancy. Benign histology shows intramural eggs surrounded by granulomatous inflammation (Image 1). Malignant histology shows keratinized nests of invasive squamous cells (Image 2).

Chronic hepatosplenic (portopulmonary) schistosomiasisHepatosplenic schistosomiasis is mainly caused by S mansoni (same distribution as S haematobium plus Caribbean and Latin America) and S japonicum (China, Philippines, Japan). Their eggs cause a range of manifestation in the liver, portal circulation, and pulmonary vessels:

- Periportal fibrosis and portal hypertension: Schistosoma eggs become trapped in the hepatic sinusoids, activating hepatic myofibroblasts (stellate cells). Periportal fibrosis obliterates the portal venules but leaves the liver parenchyma intact. This leads to noncirrhotic portal hypertension, in which patients develop manifestations of portal hypertension (eg, gastroesophageal varices, splenomegaly, ascites) but generally have no evidence of liver dysfunction (eg, they have normal coagulation studies and bilirubin levels).

- Pulmonary hypertension: Portosystemic shunting can allow Schistosoma eggs to bypass the liver and lodge in the pulmonary capillary bed. Over time, the eggs induce proliferative lesions (eg, neointimal hyperplasia, muscularis thickening) that obliterate the pulmonary arterial lumen, leading to increased vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Schistosomiasis is believed to be the leading cause of PAH worldwide (versus left-sided heart disease in the US). Patients present with exertional dyspnea and signs of right ventricular failure.

Like hepatosplenic disease, intestinal schistosomiasis is principally caused by S mansoni and S japonicum. It involves Schistosoma eggs embedding into the mesenteric vessels and bowel wall. Manifestations include abdominal pain and chronic diarrhea. Ulceration and chronic bleeding can occur, leading to iron deficiency anemia. Fibrotic complications include malabsorption and intestinal structures. Gut (and urinary) mucosal barrier breakdown can lead to spontaneous bacterial translocation (eg, Escherichia coli) and sepsis.

NeuroschistosomiasisSchistosoma larvae can travel via the cerebral and spinal arteries to the central nervous system. A small burden of eggs can cause major neurologic complications due to inflammation in a closed space. Spinal cord involvement (eg, transverse myelitis, spinal meningitis) is more common than cerebral disease (eg, inflammatory brain mass). In resource-limited countries, spinal schistosomiasis is likely responsible for ~10% cases of paraplegia.

Diagnosis

For all forms of chronic schistosomiasis, diagnosis typically begins with serology (IgM or IgG against egg and worm antigens). Due to its very high sensitivity, negative serology should prompt investigation for other causes. For patients with positive serology, active infection can be confirmed by observation of schistosomal eggs in the urine (eg, S haematobium) or stool (eg, S mansoni, S japonicum). Urinary antigen testing is also widely available (eg, dipstick), and nucleic acid-based techniques (eg, PCR) are sometimes necessary for cases with low parasite or egg load.

Management

Schistosomiasis involves an inflammatory and an infectious component; therefore, treatment generally involves prednisolone (a glucocorticoid) and/or praziquantel (an antiparasitic drug). Praziquantel works by causing massive calcium influx into the worm body, causing paralysis and detachment, allowing expulsion from the patient. It is only effective against adult worms.

- Acute schistosomiasis syndrome: The goal is to reduce the systemic inflammatory response and kill adult worms before they establish chronic infection. Treatment involves 3 steps:

- Initial glucocorticoids (eg, oral prednisolone) to reduce inflammation.

- Single dose of praziquantel to kill adult worms, often with corticosteroids overlapped to limit inflammation from parasite death.

- Second dose of praziquantel 4-6 weeks later to target remaining adult worms that were larvae at the time of the first dose.

- Chronic (urinary, hepatosplenic, and intestinal) schistosomiasis: Treatment involves a single dose of praziquantel.

- Neuroschistosomiasis: Treatment involves immediate glucocorticoids to reduce spinal cord and brain inflammation. After several days of corticosteroid therapy, praziquantel (single dose) can be safely given without exacerbating edema. Corticosteroids are usually tapered over several months.

Systemic corticosteroids are effective in schistosomiasis because the disease is caused by egg-induced granulomatous inflammation rather than worm multiplication, unlike in other helminth infections where immunosuppression can trigger parasitic dissemination (eg, Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome).

In all cases, parasite eradication should be confirmed 4-6 weeks after the final dose of praziquantel. This is accomplished with examination of urine or stool for nonviable (ie, empty) eggs. Proof of cure is important because late complications of schistosomiasis (eg, hydronephrosis, portal hypertension, PAH) are generally irreversible due to extensive fibrosis and tissue remodeling.

Summary

Schistosomiasis (Table 1) is a parasitic infection caused by Schistosoma flatworms (flukes) that infect humans through contact with contaminated water. Clinical disease is caused by Schistosoma eggs that induce granulomas, inflammation, and fibrosis in target organs. Major sites affected include the bladder, liver, intestines, and lungs. Clinical manifestations include acute schistosomiasis (fever, eosinophilia, arthralgias, migratory pulmonary infiltrates) following initial infection, urinary schistosomiasis (inflammation, hematuria, obstructive uropathy, bladder carcinoma), hepatosplenic schistosomiasis (noncirrhotic portal hypertension, pulmonary hypertension), intestinal schistosomiasis (chronic diarrhea, iron deficiency anemia), and neuroschistosomiasis (myelitis). Diagnosis is based on serology and detection of eggs in urine or stool. Treatment typically involves a systemic glucocorticoid to control inflammation and praziquantel (anthelmintic) to eliminate adult worms. Early treatment is critical because late-stage complications (eg, portal hypertension) are often irreversible.

Continue Learning with UWorld

Get the full Schistosomiasis article plus rich visuals, real-world cases, and in-depth insights from medical experts, all available through the UWorld Medical Library.

Images