Clostridioides Difficile Infection

Article Sections

Introduction

Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is a gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium responsible for causing infectious diarrhea, particularly following recent antibiotic use. Health care–associated transmission related to hospitalization is also common, and patients in rooms previously occupied by infected individuals are at increased infection risk. C difficile is shed by infected or colonized individuals, and spores can survive on surfaces for several months.

Pathophysiology

The administration of antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, fluoroquinolones, broad-spectrum penicillins) that are lethal to other commensal gut organisms can result in C difficile colitis due to an unchecked replication of pathogenic strains of C difficile.

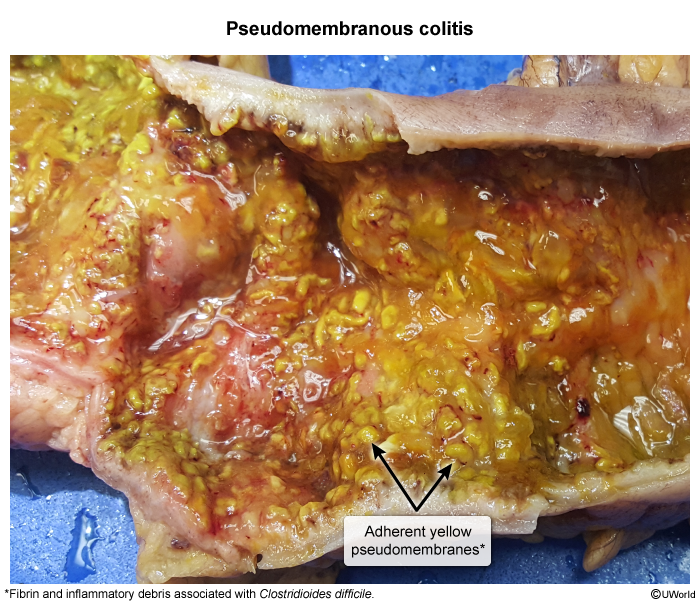

These strains produce toxin A and toxin B, which act synergistically, although toxin B is significantly more virulent. The toxins bind specific receptors on intestinal mucosal cells and are internalized, allowing them to inactivate the Rho-regulatory proteins involved in the maintenance of actin cytoskeletal structure. The result is loss of cytoskeleton integrity, leading to cell rounding/retraction, disruption of intercellular tight junctions, and increased paracellular intestinal fluid secretion (eg, watery diarrhea). Both toxins also have inflammatory effects (eg, neutrophil recruitment) and can induce apoptosis, resulting in pseudomembrane formation.

Continue Learning with UWorld

Get the full Clostridioides Difficile Infection article plus rich visuals, real-world cases, and in-depth insights from medical experts, all available through the UWorld Medical Library.

Unlock Full AccessFigures

Images