Small Bowel Obstruction

Article Sections

Introduction

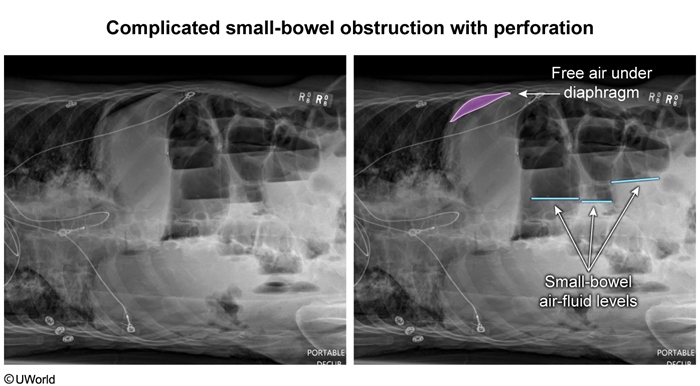

Small bowel obstruction (SBO) occurs when a mechanical blockage limits or stops the forward flow of intestinal contents, often in patients with prior abdominal surgery. Signs and symptoms of SBO typically include severe, colicky abdominal pain; vomiting; distension; diffuse tenderness; and hyperactive bowel sounds. Dilated small-bowel loops with multiple air-fluid levels and a defined transition point are characteristic imaging findings and help differentiate SBO from large-bowel obstruction. Most cases of SBO can be managed initially with conservative measures (eg, bowel rest), but complications such as bowel perforation or ischemia warrant urgent surgery.

Pathogenesis

SBO occurs when a mechanical blockage prevents the passage of fluid and gas through the gastrointestinal tract. The impaired transit of intestinal contents causes the proximal bowel to dilate and the distal bowel to collapse. Obstructions can occur from an intrinsic blockage (eg, intraluminal mass) or extrinsic compression of the bowel (eg, adhesions), and are classified as either:

- Partial: Some enteric contents can pass through a narrowed lumen, but flow is impeded. Patients may pass flatus but often cannot pass stool.

- Complete: Absence of fluid/air distal to the obstruction indicates complete obstruction and increases the risk of complications (eg, perforation). Patients are unable to pass flatus or stool.

The location of the obstruction within the small bowel affects the clinical pathology as follows:

- Proximal SBO (particularly if a complete obstruction) can cause significant gastric distension and intractable nausea and vomiting; these patients often develop dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities (eg, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis).

- Mid or distal SBO, which blocks a larger portion of the small intestine, typically presents with significant abdominal distension, colicky abdominal pain, delayed vomiting, hyperactive bowel sounds, and dilated bowel loops on imaging.

SBO leads to accumulation of fluid and gas in the bowel proximal to blockage. This causes bowel dilation and increased intraluminal pressure, which can result in:

- Bowel wall edema and compromised blood flow, leading to ischemia, necrosis, and perforation

- Bacterial overgrowth and translocation into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of sepsis

- Dehydration due to third-spacing of fluids into the bowel wall and lumen

Risk factors

Common risk factors for SBO include:

- Adhesions: From previous abdominal or pelvic surgeries.

- Hernias: Bowel that becomes entrapped within inguinal or abdominal wall hernias.

- Tumors: Primary malignancy or metastatic lesions that can extrinsically compress the bowel.

- Inflammatory bowel disease (particularly Crohn disease): Poorly controlled inflammation that leads to the formation of fibrotic strictures.

- Foreign bodies: Swallowed objects, bezoars that obstruct the intestinal lumen.

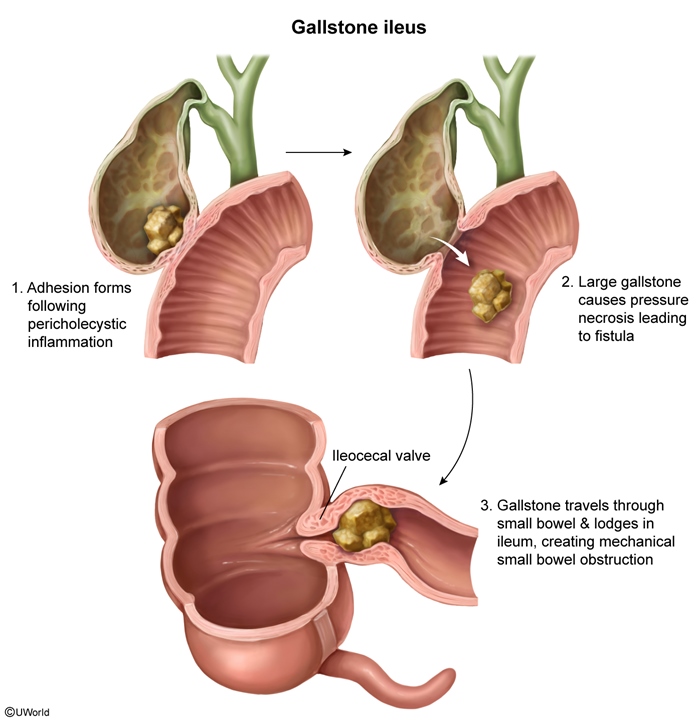

- Gallstone ileus (Figure 1): Large gallstone that erodes through the gallbladder wall into the intestinal lumen causing bowel obstruction, most often at the ileocecal valve.

- Volvulus: Twisting of the bowel on itself, which often occurs in elderly, debilitated patients.

- Intussusception: More common in children, in which a segment of bowel telescopes into another.

Clinical presentation

The clinical presentation of SBO can vary based on location and completeness of the obstruction, but typical symptoms include:

- Colicky abdominal pain: Intermittent crampy pain due unproductive bowel peristalsis against the obstruction. In complete obstructions, pain may become more constant.

- Nausea and vomiting: Vomiting, which is more prominent in proximal obstructions and occurs early in the course of disease.

- Abdominal distension with tympany: More pronounced in distal obstructions.

- Obstipation: Complete inability to pass flatus or stool, indicates complete obstruction.

- Bowel sounds: High-pitched (due to lumen narrowing) and hyperactive early in the course of obstruction; later become absent as bowel function decreases.

- Dehydration: Tachycardia, hypotension, dizziness, dry mucous membranes.

Differential diagnosis

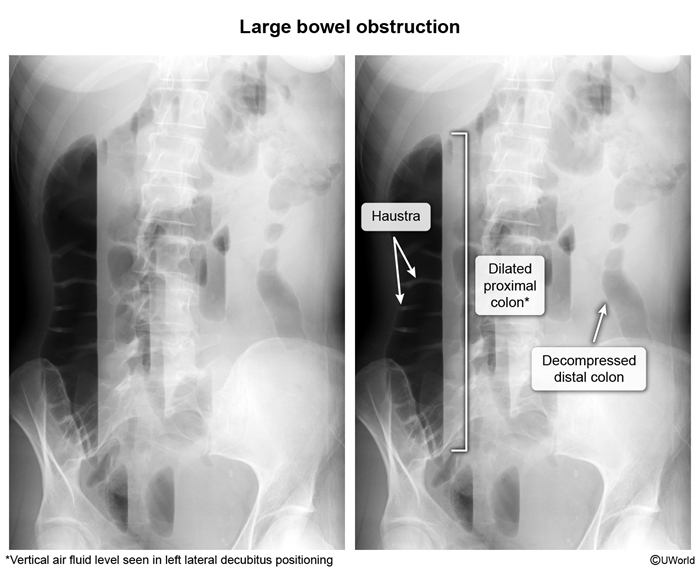

- Large-bowel obstruction (Image 1): Most often caused by tumors; patients have abdominal distension, pain, and nausea, but the onset of symptoms is typically more gradual than in SBO. A transition point in the colon (rather than the small bowel) and prominent colonic distension differentiate the conditions.

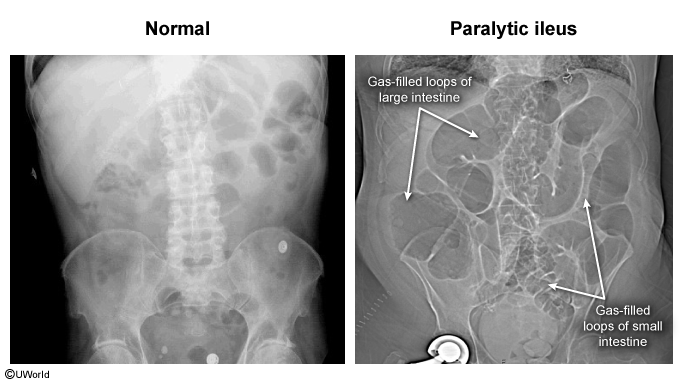

- Paralytic ileus (Image 2): Disruption of bowel motility (often postoperatively) that causes intestinal dilation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Unlike SBO, bowel sounds are typically hypoactive and abdominal pain is constant and mild (rather than colicky and severe). Radiography demonstrates uniformly dilated loops of small and large bowel with no transition point.

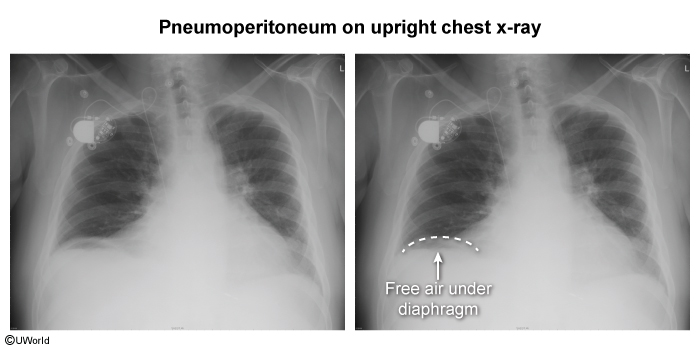

- Perforated peptic ulcer (Image 3): Leads to acute, severe epigastric pain that soon becomes generalized as stomach and intestinal contents cause peritonitis. Plain films typically show free air under the diaphragm.

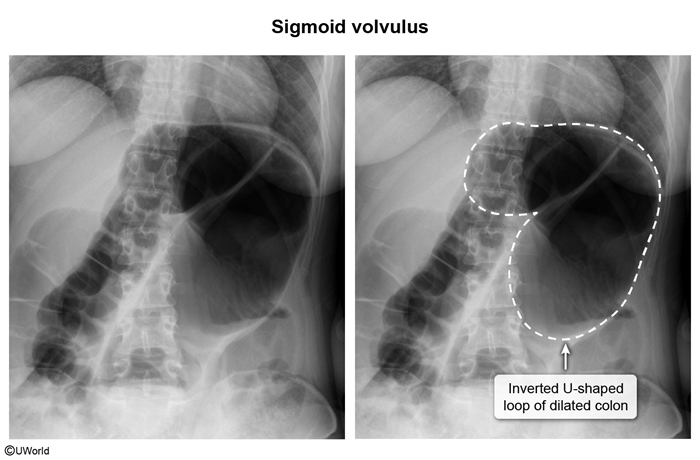

- Sigmoid volvulus (Image 4): Presents with progressive abdominal pain, obstipation, nausea/vomiting, and abdominal distension. However, abdominal x-ray reveals an inverted, U-shaped, dilated colon with little/no rectal gas. The condition occurs most often in elderly patients with limited mobility or those with an underlying neurologic disorder.

Diagnosis

SBO is typically suspected based on risk factors (eg, prior abdominal surgery) and characteristic clinical findings, including colicky abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, obstipation, and hyperactive bowel sounds. Imaging (eg, abdominal CT) confirms the diagnosis and provides details about the location/severity of obstruction and associated complications (eg, perforation).

Laboratory evaluation

The following tests are typically obtained when evaluating a patient with SBO:

- Complete blood count: Leukocytosis may indicate bowel ischemia or acute infection; anemia can occur with occult bleeding from a gastrointestinal malignancy/mass.

- Serum electrolytes: Abnormalities, such as hypokalemia, are common due to vomiting and third spacing.

- Renal function: Severity of dehydration should be determined.

- Lactate: Elevated in cases of bowel ischemia or necrosis.

- Arterial blood gas: Metabolic acidosis can result from lactic acidosis; vomiting can lead to metabolic alkalosis.

Imaging studies

The initial radiologic evaluation is typically an abdominal x-ray because it is rapidly and easily obtained. Characteristic findings include:

- Dilated loops of small bowel with multiple air-fluid levels: An upright image (or lateral decubitus) is most useful for visualizing air fluid levels.

- No gas in the colon suggests complete obstruction.

CT scan of the abdomen is the gold standard for imaging SBO because it confirms the diagnosis and provides additional details, including:

- Site of obstruction (ie, transition point where dilated bowel becomes collapsed).

- Potential etiology (eg, adhesion, hernia, tumor).

- Complications (eg, bowel ischemia, perforation).

- CT can also distinguish partial SBO from paralytic ileus; although they present similarly, ileus typically has uniform dilation of small and large bowel, air in the colon, and no transition point.

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate children or pregnant patients with possible SBO. It can be especially helpful in identifying cases of intussusception or volvulus.

Management

Many cases of SBO resolve spontaneously and can be managed nonoperatively with conservative measures and serial monitoring.

- Bowel rest: Oral intake should be restricted to reduce further bowel distension.

- Nasogastric tube decompression: Helps alleviate distension, nausea, and vomiting by draining gastric contents.

- Intravenous fluids/electrolyte replacement: Reverse losses from emesis and third spacing.

- Analgesia: Opioid use should be limited due to its potential to worsen bowel motility.

- Surgical consultation: Surgical intervention may not be required, but should be prepared for if symptoms worsen.

The following complications are surgical emergencies that necessitate immediate operative intervention, as they carry a high risk of mortality without emergency treatment:

- Bowel ischemia and necrosis: Clinical indicators include fever, leukocytosis, lactic acidosis, and pneumatosis intestinalis.

- Perforation (Image 5): Identified by free air under the diaphragm and diffuse peritonitis (eg, rigidity, rebound tenderness).

Prompt surgical intervention (eg, after adequate resuscitation) is indicated in the following circumstances:

- Closed loop obstructions (ie, two points of obstruction along a stretch of bowel): Can rapidly become ischemic, so early intervention is essential.

- Reversible causes of SBO: Hernia, gallstone ileus, foreign body, volvulus.

Surgery may also be indicated for patients who fail to improve after a trial of conservative measures.

Prognosis

Uncomplicated SBO treated conservatively often has a good prognosis. However, complications such as bowel ischemia, necrosis, or perforation can lead to significant morbidity and mortality if not treated promptly.

Prevention

Prevention strategies include minimizing postoperative adhesion development (by using minimally invasive techniques whenever possible), early hernia repair, and close monitoring of at-risk patients (eg, Crohn disease, previous SBO) for any signs of obstruction, as early recognition can limit complications.

Summary

Small bowel obstruction (Table 1) occurs due to a mechanical blockage that prevents the forward flow of intestinal contents. Bowel dilation proximal to the obstruction leads to abdominal distension; severe, colicky abdominal pain; nausea/vomiting; obstipation; and hyperactive bowel sounds. The diagnosis is confirmed by imaging that reveals dilated small bowel loops with air fluid levels and a transition point. Initial treatment is conservative, but surgery may be necessary if perforation or bowel ischemia occur.

Continue Learning with UWorld

Get the full Small Bowel Obstruction article plus rich visuals, real-world cases, and in-depth insights from medical experts, all available through the UWorld Medical Library.

Figures

Images